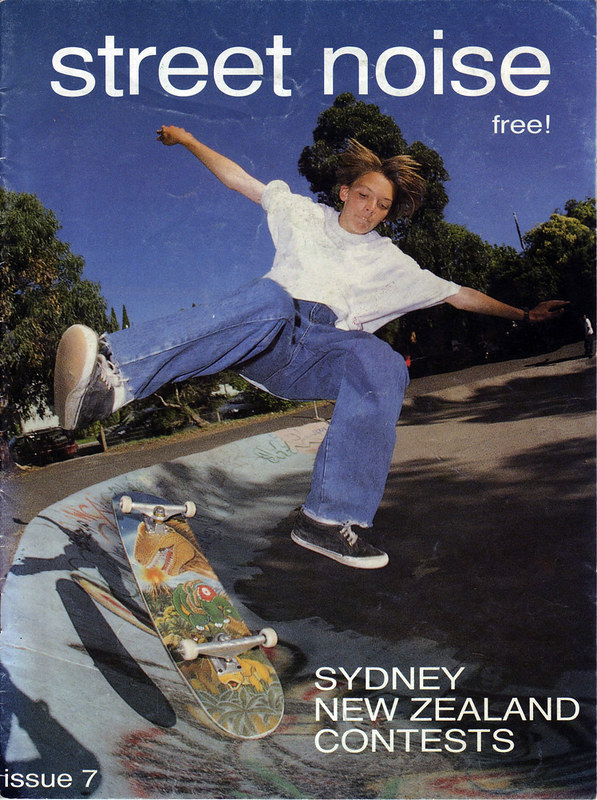

At just 20 pages (half of them ads), issue seven of the free Melbourne-based zine street noise (published in late 1992, I think) is a succinct yet dense read. Full of in-jokes and shameless self-promotion, it’s a perfect document of the early nineties and something I’m glad I’ve held onto.

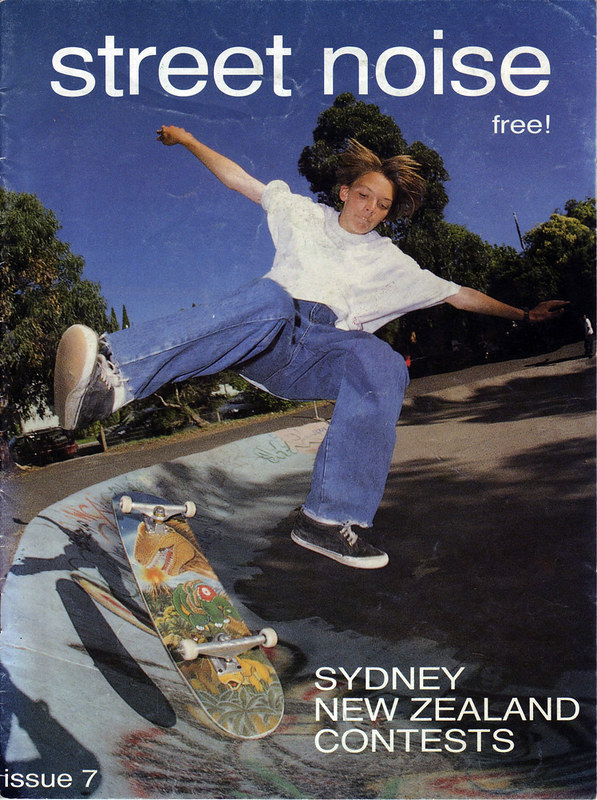

A young Ben Harris graces the cover with arguably the strongest image from the magazine’s short history. He is a sparkling Aryan poster boy for the era, wearing what I assume to be Blind jeans with torn hems, a fresh white t-shirt and well-worn Vans chukkas. His varial heel (at Prahran, where else?) shows off a brand new Daewon World Industries slick deck. How I studied this image. To this day, I’m afraid to approach Ben, or indeed any of the skaters of his ilk. They’re just too damned fresh.

Note the lowercase sans serif font, keeping with the no-fuss aesthetic of the times. Next to no information is given, but much is implied.

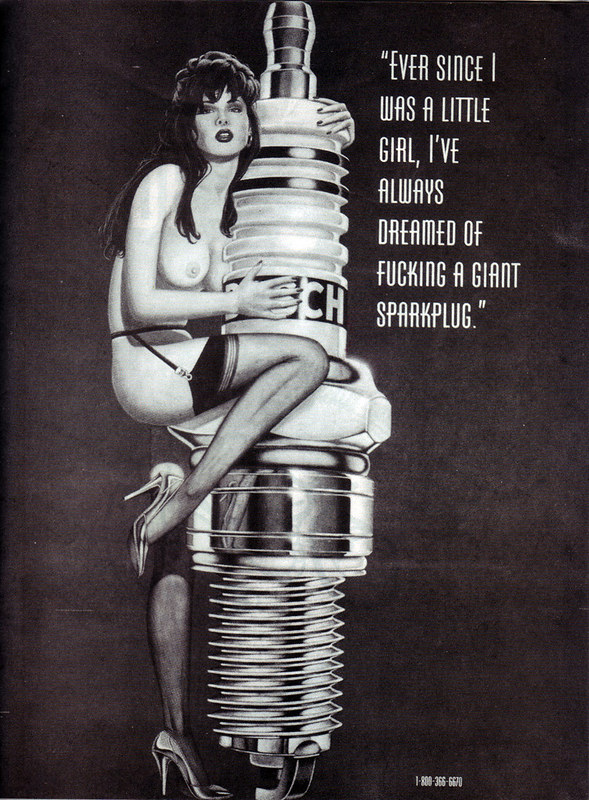

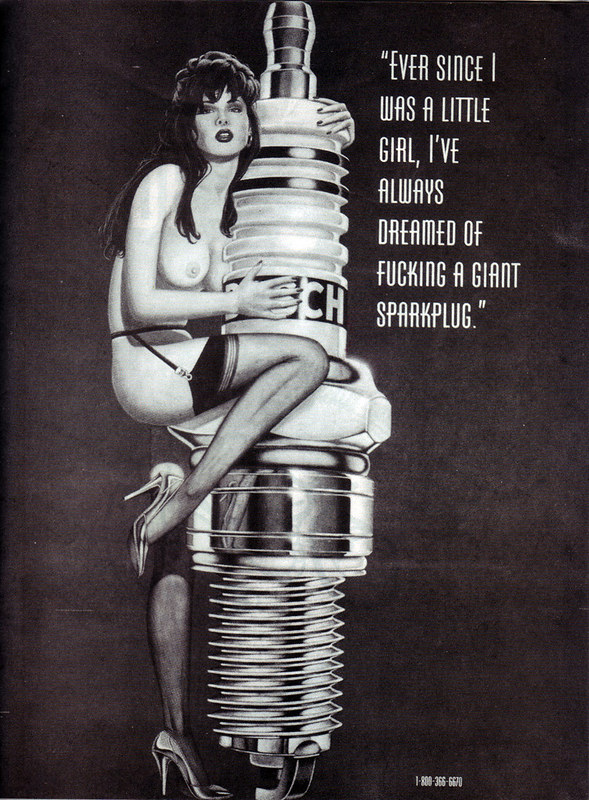

The next few pages are dedicated to advertising – an approximation of a ‘real’ magazine, though this was really a promotional publication for the pre-Globe Hardcore Enterprises umbrella of companies. I mean, Mooks? That was always a hard sell. The featured Blind Rudy Johnson sparkplug graphic was definitely a favourite amongst us pimply faced groms – the perfect combination of nudity and American cultural references. We pretended to get the joke and did our best to gather background information on the racy, obscure subject matter depicted on our boards, ranging from L. Ron Hubbard book covers and accidental gun deaths to malt liquor bottles and troll dolls.

Kerry Fisher gets the contents page with a lofty Japan air over the hip at Dulwich Hill, an impressive feat considering the miniscule radius of his wheels. I didn’t care much for his Lakers cap, though. There’s a wrap-up of the New Zealand skate scene, with mentions of the Mapstone brothers, Chey Ataria and an intriguing nod to Spittle, who in spite of ‘problems with the demon drink’ was witnessed tailsliding over a channel wearing slippers. There’s a photo of someone jumping down a flight of stairs, with no mention of who the skater is. It’s one of a few little mistakes within the issue, which only adds to the proud unprofessional stance of the magazine. They simply don’t care about spelling and being thorough and gay shit like that.

On the next page is an ad promoting the Hardcore Easter Tour (more no frills design work) that didn’t visit anywhere near where I lived and a double page spread of assorted Hardcore team riders. Among them is Greg Stewart stylishly (switch?) backside flipping down the long three on St Kilda Road, and Ben ‘Mr. S’ Pappas reclining on the deck of a vert ramp in a loose knit turtleneck jumper. I remember puzzling over the photo, recognizing Ben as an authority figure but questioning the validity of the strange sweater. Perhaps it was borrowed? Or supplied by Mooks? Brother Tas makes his first appearance in the issue with an ollie at a freshly poured Fitzroy bowl, along with the miniscule and always interesting Davo, who five-o grinds down a handrail.

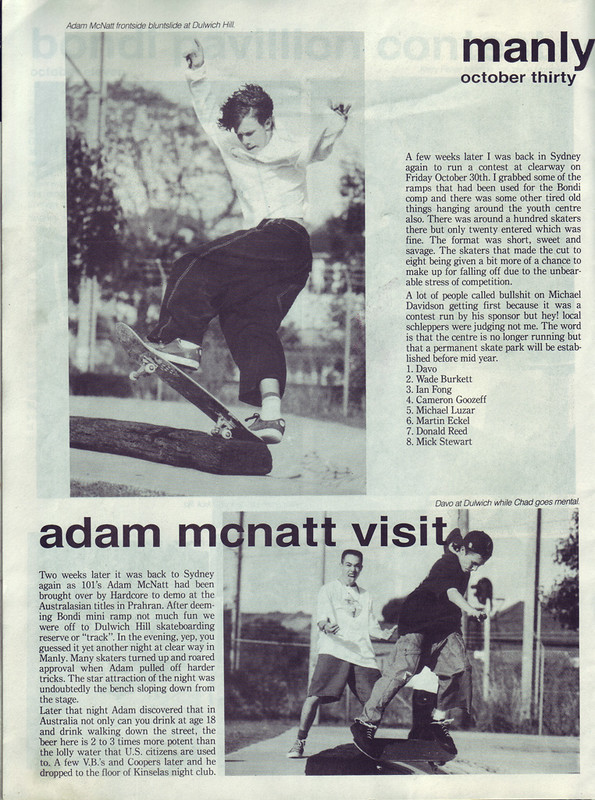

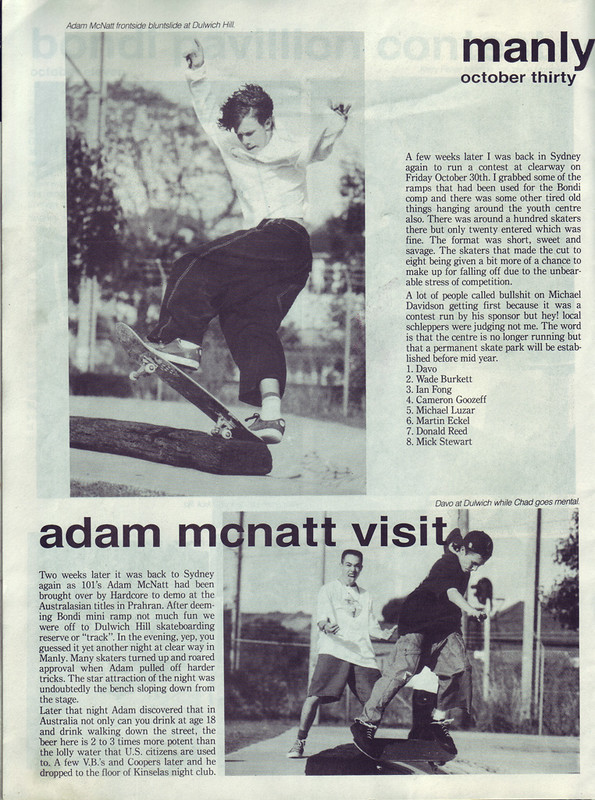

There are a few contest articles with photos that are mainly shot at street spots after the event, or in the nearby parking lot. Davo pops up a few times, as does visiting pro Adam McNatt, frontside bluntsliding two separate ledges in huge (and therefore interesting) Fuct jeans and hard-to-get Puma Clydes. The copy is nice and bitchy, with references to alleged corruption in the contest judging, gang fights and underage drinking.

The ahead of his time Ryan Denereaz receives a sequence at the exhibition buildings ledge, then there’s a shameless self-serving ‘product review’ column, including Hardcore’s own 40mm hard knobs wheels and the only truck to be seen with: Venture Featherlites.

That just about wraps it up, save another full-page photo of Tas Pappas, a deeply unfashionable Split clothing ad featuring Chris LeBlanc (remember him? Me neither). The back cover goes to a green jumbo cord sporting Davo, promoting the aforementioned hard knobs. Transparent.

The contrast of this slim publication to, say, a Skatin’ Life of merely a year or two beforehand was dramatic. The street skaters had taken over the asylum, rendering the flamboyant Ramp Riot rock stars of the previous decade hopelessly irrelevant. The early nineties are almost universally regarded as a low point for skateboarding, but street noise tells the other side of the story. It was a time of relentless innovation and enthusiasm, the birth of a more interesting and sarcastic approach that molded skateboarding (and through the ripple effect, wider popular culture) as we know it today. And above all, it was a time of big pants. Really big pants.

Max Olijnyk, May 2013